“Coconut Head” Corruption

“There is no good name for a terrible disease” – Urhobo proverb.

“The solution to Africa’s problems lie solely in Africa” – George Ayittey.

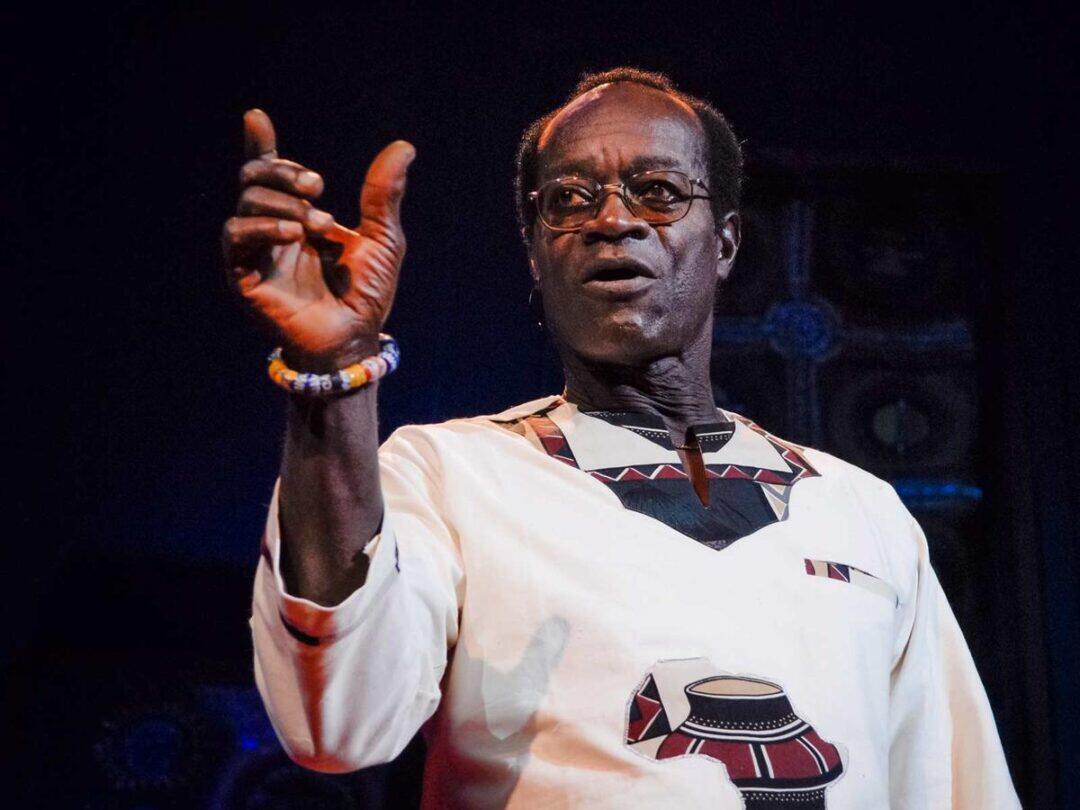

Coconut Head Corruption (CHC) is a term derived from the vocabulary of George Ayittey. He is a distinguished U.S. based Ghanaian economist and is used to describe the observed hollow-headedness and thoughtlessness exhibited by corrupt African leaders and their clients. These Big Men Ayittey is critical of have engaged in corruption since the beginning of the post-colonial era. Ayittey consistently and emphatically in his works and on social media uses words like “Coconut Leader”, “Coconut combat” or “Coconut solutions” to address misgovernance and lousy leadership in African.

Coconut-prefixed words as Ayittey uses them are just one aspect of the sincere, blunt and uncompromising zeal with which he opposes to corruption and deliberate under-development in Africa. Solving Africa’s problems is not a ‘popularity contest’; it is about consistent successful approaches and outcomes; political correctness has done nothing for Africa (Ayittey, 1992). If a definition is to be put to it, Coconut Head Corruption would be “the misuse of office by ‘Coconut heads’ for private gain”.

Ayittey is also very much an energetic opponent of the heinous consequences of corruption in Africa (Ayittey 1992, 2002, 2005, 2006), which includes incapacitating burdens of debt (Ayittey 1988, 1992b, 1999, 2002, 2005), the worst experiences of poverty known to humankind (Ayittey 1987, 1992, 2002), a lack of enforceable institutions (Ayittey 1992, 2006, 2006b, 2012). Also, poor or non-existent but necessary public services and goods (Ayittey 1992, 2002, 2005, 2012b), the suppression of free speech and freedoms (1992, 2006, 2012c), the lack of sustainable [free] trade (1992, 2002, 2005) a lack of prudent saving of GDP sufficient to foster sustainable economic growth (1992), the suppression of wilful democracy (Ayittey 2005, 2012, 2012c) and more all because Africa’s leaders put the theft of their treasuries incomparably before the interest of bettering their societies they are installed to govern (Ayittey 1992, 1999, 2002, 2005, 2006).

“Coconut Head” is precisely synonymous with the words “unwitting”, “idiot” and “senseless” and their adjectival forms. Symbolically, the coconut is mostly hollow, the very antithesis of a living human head packed ingeniously with complex networked brain cells. Ayittey’s vocabulary offends many African intellectuals who he affirms are complicit in the de-civilisation of Africa. Yet, he remains undeterred (Ayittey, 1992, 2012). Ayittey makes clear distinctions between “African leaders” and “African peoples”; the former predatory Coconut Heads and the latter a victimised and traumatised people who deserve far much better. How can the powerless be guilty of the crimes of the powerful in governance? (see Nane 2015) The symbolism of the coconut head is powerful in demonstrating thoughtlessness or irrationality in persons. “Coconut Head Corruption” is, therefore, that of the idiotic or unwitting kind (see 1992, 2006, 2006b). It necessitates a question that would raise the possibility of the notion of wise corruption. Philp (1997) is justified in rigorously questioning the basis for the notion of corruption-free politics, but it becomes challenging when the notion of foolish corruption is to be constructed and tested with rigour.

There is evidence that some Asian nations have achieved high economic growth despite simultaneously experiencing high levels of corruption (Rock & Bonnet 2004; Huang 2016). We have suggested it occurs, first, because of the existence of “value-adding corruption” and the production of net economic gains (Khan 1996). In Africa, corruption is mainly value-subtracting and the financial losses atrocious (Ayittey 1992). Second, it is because of the presence of virulent ‘roving bandits’ who have short-term access to state resources which has become a path-dependent incentive for politicians and officials to steal as much as they can while in office (Rock & Bonnet 2004; Kangoye 2013).

The existence of decidedly barbarous, Coconut Heads as dictators that are impervious to reason and heavy-handed towards the political opposition and the masses ensures that democracy does work in Africa. Without freedom, how is Africa expected to develop and prosper? He affirms this by stating “It takes an intelligent or smart opposition to make democracy work” (Ayittey, 2012c, 4). It implies that the opposition is often Coconut Heads too, operating with weak and vulnerable political strategies the dictators can undermine with relative ease. Ayittey asserts Africa’s indigenous agents and architects of its rapacious continental self-destruction as “Coconut Leaders” with “Coconut Mentalities”; “… a disgusting assortment of military coconut-heads, quack revolutionaries, crocodile liberators, “Swiss bank” socialists, and brief-case bandits. Faithful only to their private bank accounts, kamikaze kleptocrats raided and plundered the treasury with little thought of the ramifications on national development” (Ayittey 2006; 464). Corruption is bliss for such coconut heads and their clients. Ayittey sees most African leaders as black neo-colonialists that replaced white ones (Ayittey, 1992).

Ayittey further questions the “wisdom” of reliance of African leaders on foreign goods, services and ideologies while under-developing their own (Ayittey, 2006b). A staunch advocate of free trade, Ayittey would love Africa to trade favourably within and with the rest of the world and achieve indigenously determined economic success. However, he observes Africa being rendered unconducive for foreign direct investment and favourable trade arrangements because of “Africa’s environment of chaos, famine, diseases, civil wars, coups, dictatorships, social disorder, corruption and collapsed infrastructure repels foreign investment” (Ayittey 2002; 7). Africa is increasingly recording net outflows of income rather than net inflows of investment. Who wants to invest in corrupt dysfunction nations made so by thieving Coconut Heads?

In his essay, cum lamentation, A Strange Case of Xenophilia (2012b), Ayittey decries how Coconut Head leaders and bureaucrats, [if not Coconut entrepreneurs who feed off patronage] crash every sector of their economies and undermine most of the local capabilities but invest their “national incomes” in safer and stable foreign economies and capabilities. Why do African leaders not build their own safe and stable societies? Coconut Head Corruption and misgovernance. Ayittey emphasises to the world that African nations can only grow if they save at least 25% of their GDP annually (Ayittey 1992). Such a policy would reduce gratuitous capital flight, encourage necessary local investment and reduce the dependence of African nations on pernicious foreign aid. Nevertheless, corrupt African leaders are nothing better than outpost manager for the IMF despite political independence (Ayittey 2006; 464).

A nation like Nigeria spends 80-90% of its annual national income, which is predominantly from crude oil sales on foreign goods and services, including the servicing of foreign loans. The rest is for looters. Even when oil price woes have produced severe shocks to the Nigerian economy, her government is comfortable in passing high-spending budgets (Fick, 2013). Foreign loans, especially from China, fuel the spending. Ayittey is highly sceptical of the trade relationship between African Coconut Heads and China, which he assesses to border on post-IMF Sino-colonialism in Africa (Ayittey, 2011, 2017).

Nigeria is a good example that represents the persistent tragic fortunes of Africa courtesy of CHC, abundant natural resources that can only produce governance failures and hell for its citizens and societies. Ayittey, like others, sees it as a problem of leadership and institutional failure (Achebe, 1984; Ayittey 1992, 2002, 2006, 2012; Rowley 2000; Ake 2001; Nane 2017). A graphic representation of institutional failure is, “In Nigeria, basically nobody trusts the system. Nobody trusts the companies. Nobody trusts the government. Nobody trusts the regulatory agencies” (Ayittey, 2006b). It is no surprise that anti-corruption campaigns in Nigeria produce messianic hopes and spectacular failures. Yet, most Nigerians see each successive Nigerian president as a “messiah”; the “good guy surrounded by bad guys” (Nane 2017) and the leader who is so infallible but his constituents are to blame for his greed and failures (Nane 2015). How about the institutions?

The problems of Africa are like coconuts. Thick insulating fibrous layers covers the problems. How do Africans exclude the husk and shell that protect the de-civilisation happening in Africa?

In essence, Ayittey critically sees the husk of the coconut as the imitation of non-African practices to cause African problems, including corruption coupled with the neglect of indigenous African institutions and negligence of robust indigenous trade mechanisms (Ayittey, 2005, 2006). Furthermore, Ayittey advocates “Intelligent Retrogression” originally advocated by Rev S.R.B. Attoh-Ahuma a turn of the 20th Century Ghanaian philosopher, which is a profound call to return to the way of life that is deeply and customarily embodied by Africans (Ayittey 2006). Hence, Ayittey affirms that indigenous institutions will serve Africa best (Ayittey 1995, 2005, 2006). He demonstrates that while the “civic” state of Somalia failed but “the indigenous traditional” counterpart succeeds (Ayittey 1994, 2004). Ekeh (1975) supports this notion by claiming that as a legacy of colonialism, members of African societies are loyal and moral towards the “primordial” [indigenous traditional] public but they are amoral towards “civic” [foreign] public [say the government apparatus]. Institutions which are implicated to be lacking in Africa can only be enforceable with if citizens customarily embody them (Hodgson 2006). Nations with the best institutions will have the best performing economies and societies (Olson 1996; Hodgson & Knudsen 2004).

The coconut [head] has no place in Intelligent Retrogression or similar [inclusive of free enterprise, social freedoms, free speech or good governance by consensus]. African ways are like full-packed produce with soft skins. Not one with such hard and protective exterior violent breakage can only access its fruit. While African societies were not traditionally based on Western-style “grand” ideologies and post-Enlightenment discourse, they were developed by genuine necessity, far-reaching consensus, consistent rights of freedom, free speech and the surpluses created by free enterprise (Ayittey 1992, 2002, 2005, 2006). It is post-colonial auto-colonialism by African leaders that has stifled the development of the continent, with governments introducing barriers to free enterprise and the expansion of unproductive state apparatus parasitic (Ayittey, 2005).

Breaking the coconut solves Africa’s several problems, especially corruption. When the coconut is broken urgency becomes necessity. The power of consensus, unalienable rights, free speech and free enterprise should return to African societies with the will produce their solutions and grow their economies by themselves. A quote from Ayittey 2006; 558) is an allegorical end to an excellent book; “Rykia Selengia, a traditional healer, passed a coconut around and around the head of her kneeling client. The coconut went around the man’s left arm, then the right, then each leg. When she handed the coconut to the client, Mussa Norris, he hurled it onto a stone. It shattered, releasing his problems to the winds (The Washington P9ost, Nov. 12, 2001, A21).”

If one wants to sincerely wants to solve the intractable problem of corruption in Africa, the coconut must be broken along with the power and excesses of the Coconut Head leaders. In Defeating Dictators, Ayittey recommends non-violent solutions rooted in proper democracy to achieve such breakage. Finally, Ayittey asserts that the Cheetah Generation [competent entrepreneurial young Africans] that see any social failing as a business opportunity will achieve this breaking of the coconut by overthrowing the strongholds of the Hippopotamus Generation [parasitic Coconut Heads]. They create endless social failures which they profit from (Ayittey, 2014). It numbered the days of the Coconut Head leader and his misgovernance, perhaps only foreign aid and mineral sales keep them in power (Ayittey 1999, 2006).

It may be easy to see why the Afro-pessimism is the ‘prevailing reality’ of the continent and Afro-optimism is an abstract wishful reverie with incomparable exceptions like Botswana. The prevailing reality of Africa is so predictable and repetitively presented with hard evidence that it has acquired a near-scientific fidelity to it. Such pessimism, according to Ayittey, is because it is insanity to repeat the same mistakes and expect different results.

Grimot Nane, Green Economics Institute

London, 21st of April 2017

References

Achebe, C, (1984), The Trouble with Nigeria, London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Ake, C (2001), Democracy and Development in Africa, Brookings Institution Press.

Ayittey, G B N (1987), Economic Atrophy in Black Africa, Cato Journal, 7, p.195.

Ayittey, G B N, (1988), Africa Doesn’t Need More Foreign Aid; It Needs Less, The Hartford Courant.

Ayittey, G B N (1992), Africa Betrayed, Palgrave Macmillan

Ayittey G B N (1992b), The Myth of Foreign Aid, New African, June 1992. (Last retrieved 20-04-2017, URL: http: //freeafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/THE-MYTH-OF-FOREIGN-AID.pdf

Ayittey, G B N (1994), The Somali Crisis: Time for an African Solution, Cato Institute.

Ayittey, G B N, (1999), Debt Relief for Africa, Testimony Before the U.S. House Sub-Committee on Africa, April 13, 1999

Ayittey, G B N, (2000), Combating Corruption in Africa: analysis and context, (In) Corruption and Development in Africa (pp. 104-118). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Ayittey, G B N, (2002) Why Africa Is Poor, in (Ed) Morris, J, Sustainable Development: Promoting Progress or Perpetuating Poverty? Profile Books: London

Ayittey, G B N, (2005) Africa Unchained, New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Ayittey, G B N, (2006), Indigenous African Institutions, (2nd Ed) Brill

Ayittey, G B N, (2006b), Nigeria’s Struggle with Corruption, Testimony before the Committee on International Relations’ Subcommittee on Africa, Global Human Rights and International Operations House Sub-Committee on Africa, US House of Representatives, May 18th 2006

Ayittey, G B N (2011), Beware Of The Dragon: Africa Should Not Look To China, IQ2 Debate at Cadogan Hall in London, England on 28th November 2011 (Last retrieved 20-04-2017, URL : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QEVZGuh988)

Ayittey, G N B (2012), We Let Africa Down Badly, An Open Letter to African Academics, Scholars and Intellectuals, (Last retrieved 20-04-2017, URL: https://grimotnanezine.com/2014/05/22/we-let-africa-down-badly)

Ayittey, G B N, (2012b), The Strange Case of Xenophilia, (Last retrieved – 20-04-2017, URL: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/usaafricadialogue/qWSmuwX7_Vg)

Ayittey, G B N, (2012c), Defeating Dictators: Fighting Tyranny in Africa and Around the World, Griffin

Ayittey, G B N (2014), The Cheetah Generation: Africa’s new hope. Retrieved December 15, 2014, (Last retrieved 20-04-2017, URL: http://freeafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/The-Cheetah-Generation.pdf)

Ayittey, G B N (2017), The Rape of Africa by China, African Times, (Last retrieved 20-04-2017, URL: https://www.africanpost.com/opinion/55-individual/1148-the-rape-of-africa-by-china.html)

Ekeh, P P (1975), Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 17 (01) pp. 91-112

Fick, M (2016) Nigeria Passes High-Spending Budget Despite Oil Price Woes, Financial Times March 23, 2016

Hodgson, G M (2006), What are Institutions? Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. XL (1)

Hodgson, G & Knudsen, T (2004), The Firm as An Interactor: Firms as Vehicles for Habits and Routines, Journal of evolutionary economics, 14(3), pp.281-307.

Huang, C J (2016), Is Corruption Bad for Economic Growth? Evidence from Asia-Pacific Countries, North American Journal of Economics and Finance 35 pp.247–256

Kangoye, T (2013), Does Aid Unpredictability Weaken Governance? Evidence from Developing Countries, Development Economics, 51, 121–144.

Khan, M (1996), The Efficiency Implications of Corruption, Journal of International Development, 8 (5), pp.683-696

Nane, G (2015) Are Leaders or Followers to Blame for Corruption (URL: http://www.academia.edu/16629331/Are_Leaders_or_Followers_to_Blame_for_Corruption)

Nane, G (2017), How Leadership Fails Nigeria, Grimot Nane Zine article (URL: https://grimotnanezine.com/2017/04/02/how-leadership-fails-nigeria/)

Olson, M (1996), Big Bills Left on The Sidewalk: Why Some Nations are Rich, and Others Poor, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(2), Pp.3-24.

Philp, M (1997), Defining Political Corruption; (In) Heywood, P (Ed.), Political Corruption, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 20–46

Rock, M T & Bonnet, H (2004), The Comparative Politics of Corruption: Accounting for The East Asian Paradox In Empirical Studies Of Corruption, Growth And Investment, World Development 32, pp. 999-1017

Rowley, C K (2000), Political Culture and Economic Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa, European Journal of Political Economy; Vol. 16, No. 1 pp. 133-58

Discover more from Grimot Nane Zine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.